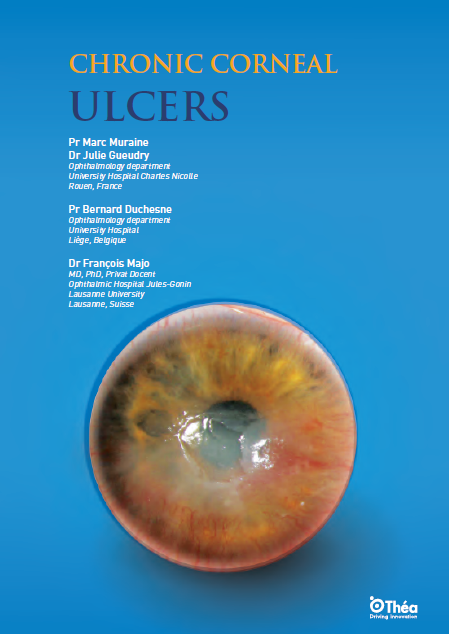

Chronic corneal ulcers are a persistent and debilitating condition characterized by the breakdown of the corneal epithelium with subsequent involvement of the underlying stroma. Unlike acute ulcers, which typically heal within a few days, chronic ulcers do not heal even after three weeks. The pathophysiology of these ulcers is complex and often involves multiple factors that can disrupt the normal healing process of the corneal epithelium.

The cornea is a transparent and avascular structure at the front of the eye, consisting of several layers, including the epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. The healing of the corneal epithelium is generally rapid, with basal epithelial cells migrating to cover the denuded area. However, when this process is disrupted, it can lead to chronic ulceration. Factors such as persistent inflammation, infection, and impaired corneal nerves can significantly alter the healing cascade, causing prolonged epithelial defects and stromal degradation.

The etiology of chronic corneal ulcers includes a range of infectious and non-infectious causes. Corneal infection such as infectious keratitis, caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites, is a common cause. Corneal pathology with non-infectious etiologies include neurotrophic keratitis, autoimmune diseases, and exposure keratopathy. Each of these causes presents distinct challenges in diagnosis and management.

Infectious causes:

- Bacterial keratitis: Common bacterial pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. These infections are often associated with contact lens wear, trauma, and prior ocular surgery.

- Fungal keratitis: Fungal infections are more prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions. Aspergillus and Fusarium species are common culprits. Fungal keratitis often follows trauma with vegetable matter.

- Viral keratitis: Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are the primary viral pathogens. HSV keratitis is known for its recurrent nature and can lead to neurotrophic ulcers.

- Acanthamoeba keratitis: This rare but severe infection is associated with contact lens wear and exposure to contaminated water.

Non-infectious causes:

- Neurotrophic keratitis: Damage to the trigeminal nerve, which supplies the cornea, can lead to reduced corneal sensation and impaired healing. Common causes include HSV infection, diabetes, and ocular surgery.

- Autoimmune diseases: Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus can cause peripheral ulcerative keratitis and scleritis, leading to corneal ulceration.

- Exposure keratopathy: Incomplete eyelid closure (lagophthalmos) due to facial nerve palsy or eyelid malposition can cause corneal exposure and subsequent ulceration.

Risk factors that enhance the likelihood of ulcer development include trauma, contact lens wear, ocular surface disease, and immunosuppression. Conditions such as herpes simplex virus infection, dry eye disease, and systemic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis can also predispose individuals to chronic corneal ulcers.

Clinically, chronic corneal ulcers present with symptoms such as pain, redness, photophobia, and decreased vision. The diagnosis involves a thorough clinical examination, including slit-lamp biomicroscopy, corneal sensitivity testing, and microbiological cultures to rule out infectious causes. Fluorescein staining is used to visualize the extent of the epithelial defect and any stromal involvement.

A diagnostic algorithm is essential when assessing chronic corneal ulcers. The initial step is to rule out infection, followed by testing corneal sensitivity to differentiate between neurotrophic and non-neurotrophic ulcers. The location of the ulcer (central, paracentral, or peripheral) and associated clinical signs help in narrowing down the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Slit-lamp examination: This is the cornerstone of corneal ulcer diagnosis. It allows for the detailed assessment of corneal integrity, the presence of infiltrates, and the depth of ulceration. The use of fluorescein dye highlights epithelial defects and areas of stromal thinning.

- Corneal sensitivity testing: Using a cotton wisp or specialized esthesiometer, corneal sensation can be evaluated. Reduced or absent sensation is indicative of neurotrophic keratitis.

- Microbiological cultures: Corneal scrapings are taken for Gram staining and culture to identify bacterial, fungal, or amoebic pathogens. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used for viral detection.

- Confocal microscopy: This advanced imaging technique provides a high-resolution view of the cornea at the cellular level, aiding in the identification of infectious agents like Acanthamoeba.

The treatment of chronic corneal ulcers has seen significant advances in recent years. The primary aim is to promote epithelial healing, prevent stromal lysis, and avoid complications such as corneal perforation, while promoting corneal healing. Discontinuation of toxic topical medications is crucial, along with the use of preservative-free lubricants.

Therapeutic options include the use of therapeutic contact lenses, autologous serum eye drops, and regenerative agents such as RGTA (ReGeneraTing Agents) eye drops. Surgical interventions like amniotic membrane transplantation, cyanoacrylate glue application, and tectonic keratoplasty can be utilized for persistent or severe ulcers.

One of the most promising developments in recent years has been the use of regenerative medicine techniques. The application of stem cell therapy, for example, aims to restore damaged corneal tissue and promote healing. Research into bioengineered corneal substitutes also holds potential for patients with extensive corneal damage where standard treatment fails.

Other Treatment Advances:

- Topical growth factors: These agents can accelerate epithelial healing and are particularly useful in neurotrophic keratitis.

- Matrix regenerating agents: RGTA eye drops mimic the extracellular matrix, providing a scaffold for cell migration and tissue regeneration.

- Anti-microbial peptides: These novel agents provide broad-spectrum activity against resistant pathogens, reducing reliance on conventional antibiotics.

- Gene therapy: Advances in gene editing techniques such as CRISPR hold promise for correcting genetic defects that contribute to corneal diseases.

Managing chronic corneal ulcers remains challenging due to the diverse etiologies and the potential for severe complications. The need for a multidisciplinary approach in ophthalmology research, including collaboration with internists and rheumatologists, is often necessary for systemic conditions associated with ocular manifestations.

Future research in ophthalmology is focused on developing targeted therapies that can modulate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Advances in tissue engineering, stem cell therapy, and novel pharmacological agents hold promise for improving the outcomes of patients with chronic corneal ulcers.

Despite these advances, there are still challenges to overcome. The development of antibiotic resistance, for instance, necessitates ongoing research into new antimicrobial therapies. Additionally, understanding the genetic basis of certain corneal conditions could pave the way for personalized medicine approaches to treatment.

There is also a need for long-term studies to evaluate the efficacy and safety of emerging treatments. As the field of ophthalmology continues to evolve, staying abreast of the latest research and developments will be crucial for clinicians managing chronic corneal ulcers.

Chronic corneal ulcers are a significant ophthalmic concern that requires a nuanced understanding of their definition, pathophysiology, and etiology. Advancements in diagnostic techniques and treatment options have improved the management of these ulcers, but challenges remain. Continued research and a multidisciplinary approach are essential to address the complexities of chronic corneal ulcers and enhance patient care.

By leveraging cutting-edge research and collaborating across disciplines, we can hope to achieve better outcomes for patients suffering from this challenging condition. The future holds promise for more effective and targeted therapies that can transform the landscape of chronic corneal ulcer management.