The anatomical conception of the eye has undergone a remarkable transformation throughout history. Early records, such as the Ebers Papyrus from 1550 B.C., reveal how ancient civilizations blended myth, medicine, and philosophy in their understanding of anatomy and physiology. In those times, the eye was often regarded as a mystical organ, with healing powers attributed to symbols like the Eye of Horus, a motif prominently featured on stamps from the 1937 Cairo Congress on ophthalmology. This symbol not only represented protection and health but also reflected the deep cultural significance of vision in ancient societies.

As centuries passed, the history of ophthalmology saw significant milestones. Medieval surgical practices began to separate superstition from science, paving the way for more systematic approaches to eye care. Notably, a stamp honoring Nicholas of Cusa commemorates his pioneering reference to concave lenses for myopia, marking a pivotal shift towards modern optical correction. Another fascinating figure is Pope John XXI, one of the few physician-popes, depicted on stamps performing lens couching, an early and bold attempt at cataract treatment.

These historical symbols and depictions capture the evolving journey from mystical interpretations to scientific exploration. The gradual shift from myth to method laid the foundation for our current understanding of the eye’s anatomy and physiology, shaping the future of ophthalmology and vision science.

Throughout the history of ophthalmology, numerous pioneers have shaped the way we understand and treat eye disease. Commemorative stamps pay tribute to these trailblazers, each representing a milestone in the evolution of vision care. Jacques Daviel, for example, revolutionized cataract surgery with the first extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE), dramatically improving patient outcomes. Albrecht von Graefe’s innovations, including the iridectomy and his insights into angle-closure glaucoma, transformed the management of complex eye conditions and deepened our understanding of the optic nerve.

Frans Cornelis Donders stands out for his groundbreaking work on accommodation, which laid the scientific foundation for the correction of presbyopia, a condition affecting near vision as we age. Meanwhile, Vladimir Filatov and Eduard Zirm made corneal transplantation a reality, restoring sight to thousands and opening new frontiers in ocular surgery.

The book also honors Allvar Gullstrand, a Nobel laureate whose invention of the slit lamp remains an essential diagnostic tool in modern eye clinics. These stamps do more than commemorate individual achievements; they trace the progress of eye disease management and the development of instruments and treatments that are still central to ophthalmology today.

For anyone interested in the rich legacy of vision science, ophthalmology books and resources from major congress events provide a deeper look at how these innovators continue to shape the future of eye care.

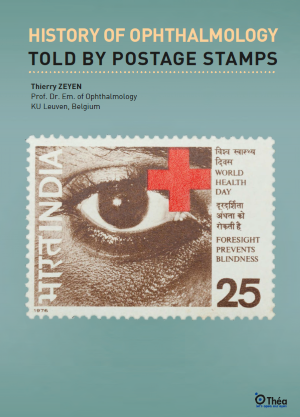

Postage stamps have long served as powerful symbols in the global struggle against eye disease and blindness. From trachoma and onchocerciasis (river blindness) to xerophthalmia caused by vitamin A deficiency, stamps have illustrated the social and medical battles waged to prevent avoidable vision loss. Each stamp not only raises awareness but also honors the collective efforts of international organizations and public health campaigns.

The depiction of cataract surgery, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma on stamps highlights the ongoing urgency of these conditions, which continue to threaten sight worldwide. By featuring these diseases, stamps remind the public that, despite medical advances, millions remain at risk of blindness due to preventable or treatable causes.

Stamps have also commemorated landmark campaigns, such as the World Health Organization’s initiatives against river blindness and the advocacy of groups like the Lions Club and the Braille League. These commemorative issues transform everyday objects into educational tools, spreading crucial messages about eye disease, myopia, and the importance of early intervention.

Beyond their biological depictions, stamps reflect the historical urgency of fighting blindness and the evolving understanding of the optic nerve and visual system. In doing so, they serve as both reminders of past struggles and beacons of hope for a future where preventable blindness is eradicated.

Throughout the history of ophthalmology, international congresses have played a pivotal role in advancing scientific knowledge and fostering collaboration. Stamps commemorating events like the International Congress of Ophthalmology and the Afro-Asian Congresses are more than just collectibles, they are enduring symbols of global scientific exchange. These congresses, celebrated through philately, highlight how ophthalmologists have long valued collaboration across borders, sharing discoveries and innovations well before the digital era made such communication instantaneous.

The cultural impact of ophthalmology extends beyond the clinic and laboratory. Figures such as L. L. Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto, Jose Rizal, the Filipino national hero and eye surgeon, and Arthur Conan Doyle, who trained in ophthalmology before becoming a renowned author, demonstrate how ophthalmologists have influenced not just medicine, but also language, politics, and the arts. Their lives, captured on stamps, show how the profession has produced individuals whose contributions transcend their medical achievements, turning them into lasting cultural symbols.

These miniature works of art, often featured in ophthalmology books and collections, remind us that the field is not only about treating disease but also about shaping society. Through science, diplomacy, and creativity, ophthalmology continues to leave its mark on the world, with congresses and cultural icons serving as milestones in its rich and diverse history.